Bengal’s sarees have carved a niche for themselves and are popular across the country and even abroad among NRIs which is probably the reason the economy of small villages like Shantipur in West Bengal’s Nadia district still survive. Tangail, jamdani and tussar silks come from this small village which houses around 1,25,000 handlooms and powerlooms.

Weaving in India has a history of no less than 5,000 years but in Shantipur it all started after the Indo-Bangla Partition. The hub was in Bangladesh and after Partition, weavers settled here and in Phulia, also in Nadia. Shantipur woke up to a new sunrise ever since the sarees started being exported. A weekly market is organised where buyers from across the country arrive to buy the six yard in bulk at a cheap rate.

WEAVING EMOTIONS

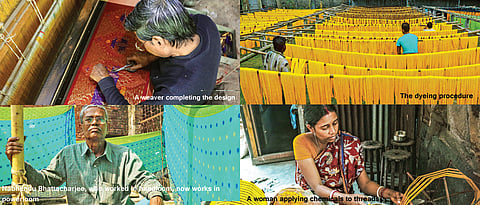

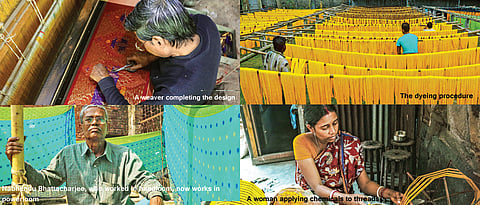

The first thing that catches a person’s attention while visiting Shantipur is the sight of bobbins spinning out colourful threads to weave what the people of the village call “emotion”. A closer look will reveal the artistry of the weavers. But all is not hunky dory in this weavers’ town.

“We had settled here after Partition and ever since, our family has been in the business of weaving sarees. However, things were different then and now, our existence is at stake,” says 57-year-old Gopal Pramanick with a sad glimmer in his eyes, adding, “We lose out on bigger opportunities as we, who run handlooms, do not have the means for mass production and that gives the powerlooms an edge over us.”

While a powerloom can produce three to four sarees a day, a handloom can make the same in a week’s time.

The weavers also talk of another problem — not getting the right value for their art. While weaving dexterously the strands of thread to create a beautiful saree, Parbati says, “It is not that we only have the problem of increasing competition from powerlooms. Our mahajans too pay us poorly and there is hardly a way to bypass them who act as our interface with the rest of the world.” The 35-year-old homemaker pitches in to the family business during her free time.

While the rate of production is high in powerlooms, it cannot match the quality, design and texture of a handloom saree, and that’s what pushes the cost up. Handloom weavers get around Rs 500-600 for one saree against a powerloom weaver’s Rs 200-300. A saree made in a handloom starts from Rs 1,000 while the same from a powerloom costs Rs 600.

However, even powerloom weavers are not happy with the current state of affairs. Sankar Basak says machines are being updated in other parts of the country but they do not have the means to afford them. Basak, who owns a powerloom, adds, “I have previously worked in handlooms and the money is more there as buyers these days are conscious of the quality and are ready to pay more.”

Echoing Basak’s thoughts, Nabhendu Bhattacharjee says that handlooms will not be thrown out of business as the rate of defective pieces is higher in powerlooms. Bhattacharjee has worked in both handlooms and powerlooms.

There is an impending crisis looming over the fate of Bengal’s weavers. However, if the number of patrons grows and, more importantly, if we can learn to appreciate our art and traditions, then perhaps the weavers will have a different story to tell in some years.